The enemy within: new research reveals insights into the arsenal Rickettsia parkeri uses against its host

Lillian Eden | Department of Biology

July 29, 2024

Identifying secreted proteins is critical to understanding how obligately intracellular pathogens hijack host machinery during infection, but identifying them is akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

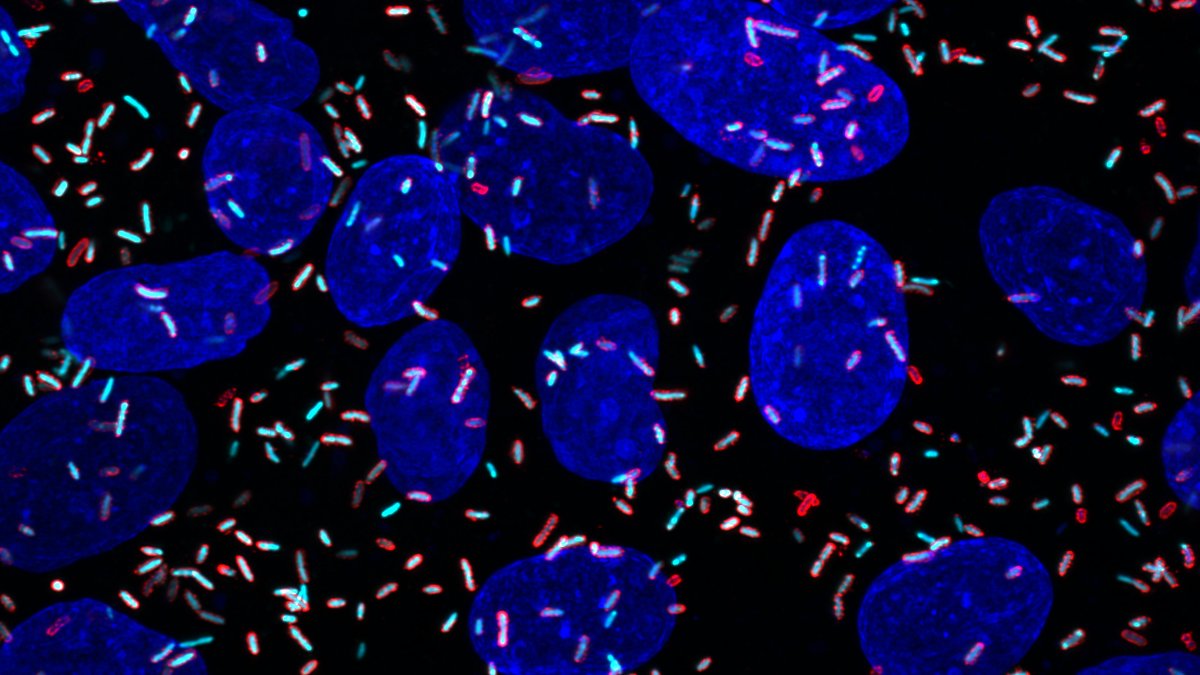

For then-graduate student Allen Sanderlin, PhD ’24, the first indication that a risky, unlikely project might work was cyan, tic tac-shaped structures seen through a microscope — proof that his bacterial pathogen of interest was labeling its own proteins.

Sanderlin, a member of the Lamason Lab in the Department of Biology at MIT, studies Rickettsia parkeri, a less virulent relative of the bacterial pathogen that causes Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, a sometimes severe tickborne illness. No vaccine exists and definitive tests to diagnose an infection by Rickettsia are limited.

Rickettsia species are tricky to work with because they are obligately intracellular pathogens whose entire life cycles occur exclusively inside cells. Many approaches that have advanced our understanding of other bacterial infections and how those pathogens interact with their host aren’t applicable to Rickettsia because they can’t be grown on a plate in a lab setting.

In a paper recently published in Nature Communications, the Lamason Lab outlines an approach for labeling and isolating R. parkeri proteins released during infection. This research reveals seven previously unknown secreted factors, known as effectors, more than doubling the number of known effectors in R. parkeri.

Better-studied bacteria are known to hijack the host’s machinery via dozens or hundreds of secreted effectors, whose roles include manipulating the host cell to make it more susceptible to infection. However, finding those effectors in the soup of all other materials within the host cell is akin to looking for a needle in a haystack, with an added twist that researchers aren’t even sure what those needles look like for Rickettsia.

Approaches that worked to identify the six previously known secreted effectors are limited in their scope. For example, some were found by comparing pathogenic Rickettsia to nonpathogenic strains of the bacteria, or by searching for proteins with domains that overlap with effectors from better-studied bacteria. Predictive modeling, however, relies on proteins being evolutionarily conserved.

“Time and time again, we keep finding that Rickettsia are just weird — or, at least, weird compared to our understanding of other bacteria,” says Sanderlin, the paper’s first author. “This labeling tool allows us to answer some really exciting questions about rickettsial biology that weren’t possible before.”

The cyan tic tacs

To selectively label R. parkeri proteins, Sanderlin used a method called cell-selective bioorthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging. BONCAT was first described in research from the Tirrell Lab at Caltech. The Lamason Lab, however, is the first group to use the tool successfully in an obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen; the thrilling moment when Sanderlin saw cyan tic-tac shapes indicated successfully labeling only the pathogen, not the host.

Sanderlin next used an approach called selective lysis, carefully breaking open the host cell while leaving the pathogen, filled with labeled proteins, intact. This allowed him to extract proteins that R. parkeri had released into its host because the only labeled proteins amid other host cell material were effectors the pathogen had secreted.

Sanderlin had successfully isolated and identified seven needles in the haystack, effectors never before identified in Rickettsia biology. The novel secreted rickettsial factors are dubbed SrfA, SrfB, SrfC, SrfD, SrfE, SrfF, and SrfG.

“Every grad student wants to be able to name something,” Sanderlin says. “The most exciting — but frustrating — thing was that these proteins don’t look like anything we’ve seen before.”

Special delivery

Theoretically, Sanderlin says, once the effectors are secreted, they work independently from the bacteria — a driver delivering a pizza does not need to check back in with the store at every merge or turn.

Since SrfA-G didn’t resemble other known effectors or host proteins the pathogen could be mimicking during infection, Sanderlin then tried to answer some basic questions about their behavior. Where the effectors localize, meaning where in the cell they go, could hint at their purpose and what further experiments could be used to investigate it.

To determine where the effectors were going, Sanderlin added the effectors he’d found to uninfected cells by introducing DNA that caused human cell lines to express those proteins. The experiment succeeded: he discovered that different Srfs went to different places throughout the host cells.

SrfF and SrfG are found throughout the cytoplasm, whereas SrfB localizes to the mitochondria. That was especially intriguing because its structure is not predicted to interact with or find its way to the mitochondria, and the organelle appears unchanged despite the presence of the effector.

Further, SrfC and SrfD found their way to the endoplasmic reticulum. The ER would be especially useful for a pathogen to appropriate, given that it is a dynamic organelle present throughout the cell and has many essential roles, including synthesizing proteins and metabolizing lipids.

Aside from where effectors localize, knowing what they may interact with is critical. Sanderlin showed that SrfD interacts with Sec61, a protein complex that delivers proteins across the ER membrane. In keeping with the theme of the novelty of Sanderlin’s findings, SrfD does not resemble any proteins known to interact with the ER or Sec61.

With this tool, Sanderlin identified novel proteins whose binding partners and role during infection can now be studied further.

“These results are exciting but tantalizing,” Sanderlin says. “What Rickettsia secrete — the effectors, what they are, and what they do is, by and large, still a black box.”

There are very likely other effectors in the proverbial cellular haystack. Sanderlin found that SrfA-G are not found in every species of Rickettsia, and his experiments were solely conducted with Rickettsia at late stages of infection — earlier windows of time may make use of different effectors. This research was also carried out in human cell lines, so there may be an entirely separate repertoire of effectors in ticks, which are responsible for spreading the pathogen.

Expanding Tool Development

Becky Lamason, the senior author of the Nature Communications paper, noted that this tool is one of a few avenues the lab is exploring to investigate R. parkeri, including a paper in the Journal of Bacteriology on conditional genetic manipulation. Characterizing how the pathogen behaves with or without a particular effector is leaps and bounds ahead of where the field was just a few years ago when Sanderlin was Lamason’s first graduate student to join the lab.

“What I always hoped for in the lab is to push the technology, but also get to the biology. These are two of what will hopefully be a suite of ways to attack this problem of understanding how these bacteria rewire and manipulate the host cell,” Lamason says. “We’re excited, but we’ve only scratched the surface.”